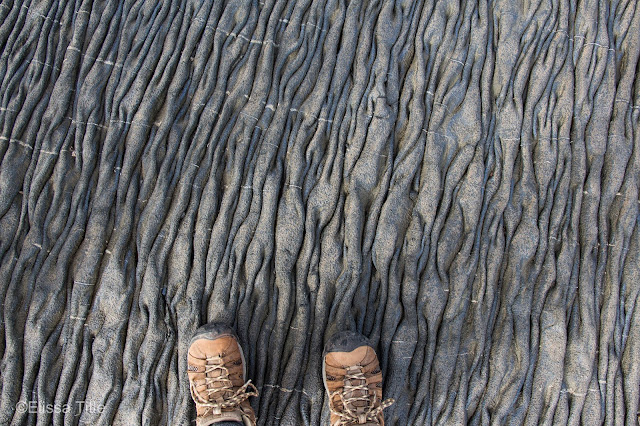

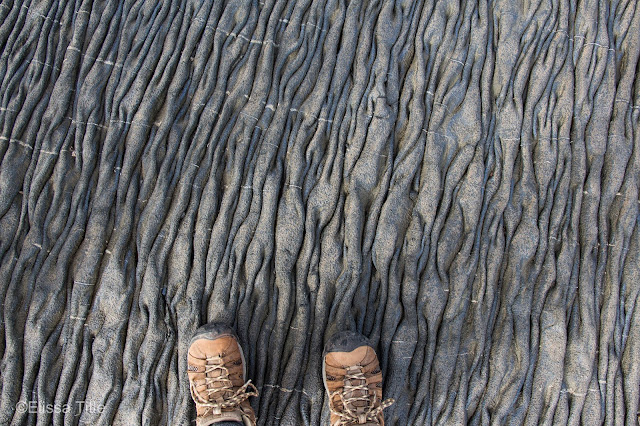

This morning we went to Sullivan Bay, located on Santiago Island (also called James Island). Sullivan Bay offers a rare look at recently-formed lava fields with pahoehoe formations of all shapes and textures. These formations are 150 years old, so Darwin did not see them when he was here. When the fluid magma emerges, it is extremely hot (about 1,100 degrees Celsius or about 2,012 degrees Fahrenheit). It flows downhill and as it flows, it cools and becomes more viscous. The more viscous it becomes, the more slowly it flows. Since the surface is in contact with air, it forms a crust as it cools. There are two majors types: rubbly surfaced "aa" (Hawaiian for "hurt") or smooth, ropey surfaced "pahoehoe" (Hawaiian for "ropey"). It is said that the pahoehoe lava flows resemble intestines, though I think it resembles a brain.

|

Hiking on pahoehoe lava formations.

|

|

|

Drowning in lava (but really just squatting in a really small hole).

|

|

A helping hand.

|

|

Some of the few plants that grow in the lava.

|

|

Sometimes, you are able to see where trees once were as the lava will flow around a tree, engulf it, and the tree will then vaporize. As the tree vaporizes, it leaves a mold of its trunk and branches. In many cases, you can still see the bark of the tree. As a result, geologists are able to identify what kind of tree was once there. This type of lava flow is not common worldwide, though it can be seen in the Galapagos and Hawaii. The aa lava flow, however, is much more common worldwide.

|

A lone tree in the lava.

|

As a graphic designer, I naturally observe shapes and textures, even subconsciously. For once, I didn't mind looking down at the ground as I watched my footing because every few steps, the lava flow changed. The colors ranged from charcoal to even including some lowly saturated rusted browns and the occasional lowly saturated greens. The variations of textures and changes in scale were truly spectacular. One minute you'd be walking on large, smooth, almost rounded areas of lava and the next moment you'd be walking along tightly roped pahoehoe with hundreds of little wrinkles. The symmetry of the lava flows would also change and while most areas were very asymmetrical, there were a few instances where the pahoehoe was perfectly symmetrical and very pleasing to the naked eye.

In one area, we were able to clearly see where the lava stopped flowing. There were light brown rocks one minute, and lava frozen in place the next. Every island here feels like another planet. Each island is like a different planet with different creatures, different landscapes, a different history, and different plants. This was the first time I felt truly remote, as I looked off into the distance only seeing lava as far as the horizon. Santiago is the fourth largest island in the Galapagos, but it felt like the largest because all I could see was lava everywhere I looked. The black lava flows made the water look even more turquoise due to the heavy contrast between dark and light. This was probably one of my favorite views of the ocean!

|

Where the lava stopped flowing.

|

In the afternoon, we went to Bartolome. . . one of the most popular sites for panoramic views. The volcanic features at this location are spatter cones, cinder cones and tuff cones. Spatter cones are formed when large amounts of gas are released and large lumps of molten material are sent skyward. These solidify and pile up to form spatter cones, which are said to resemble cow-pats. However, sometimes the volcanic eruption has insufficient material to form a lava flow in which case the result is an unbroken spatter cone (like on Bartolome Island). Cinder cones, also called scoria cones, form by the explosive ejection of solid rock. The large amounts of rock are thrown high into the air, eventually falling to the ground at varying distances from the vent. Tuff cones are found near the coasts, offshore from the volcanoes. These cones are formed from smaller, ash-sized particles when compared to the scoria cones. The interactions of molten rock and water causes explosions, which then cause highly fragmented material to be flung far away. The particles forming an ash ring become harder rocks, called tuff, which is how the tuff cone got its name.

To get to the panoramic views, you have to climb 365 stairs. Our naturalist Martin said that to make the hike go faster, we should count to our birthday. When we reach the step with our birthday, we should mark it in pen as many others have done before us. The stairs were apparently built at different intervals, some 20+ years ago and some as recent as 2-3 years ago. When he told us there were 365 stairs, I was expecting it to be a lot worse. The stairs were broken up by viewing platforms, where we could see the entire bay below. This was the first time we saw many other people and even though we were still remote, it somehow felt more civilized. The view from the top was gorgeous with the sun beams slicing through the cloud cover illuminating the land and water below. We had a lovely view of Pinnacle Rock.

|

The start of the path to the top of the hill... No stairs yet!

|

|

Nearing the top of the hill, I took a minute to look back down.

|

|

View from the second highest viewing platform.

|

|

The last remaining steps to the top.

|

|

| Panorama from the top. |

Along the side of the path was tiquilia, a small herb that forms shrubs. These plants live in very dry conditions and it is often the only species of plant found on ash-covered talus slopes such as Bartolome. Lava lizards eat its flowers and insects visit the plants as well. It is a very simple ecosystem, but it is an ecosystem nonetheless. Our naturalist Martin was also telling us how even movie filming is regulated. For instance, the entire camera had to remain on the platform/viewing point. The actor was permitted to go off the trail, but at a minimal distance. The actor's footprints lasted for five years. This concept of filming in the Galapagos got me thinking. As the Galapagos grows in popularity, will more people want to film here? How will the government and conservation officials decide who can go off trail, and for how long? The Galapagos is so beautiful because it is fairly untouched by humans but how long will that last? The Galapagos is already changing. As tourists harm the environment, new laws and regulations are put in place. When I was here in 2004, we were able to walk right up to the tortoises as we do with sea lions. I have a photograph of me a foot away from Lonesome George. Now, the tortoises are kept in a zoo-like setting where tourists can't harm them. I hope this is not the case, but I think at some point humans will destroy the Galapagos. We never realize how vulnerable and valuable things like the Galapagos are until its past the point of no return. . .

That's all for now... Stay tuned for more Galapagos adventures. Also, be sure to hit the subscribe button to be notified of new posts, as there is sometimes unreliable internet! Follow my instagram @elissatitle for more photography posts.

Comments

Post a Comment